Designing Project & Presentation Assessments

Here, we define a project as a summative assessment that allows students to apply the skills from multiple objectives. Generally, students have weeks or months to complete a project, differentiating it from homework or other types of assessments.

Projects designed for traditional grading classrooms often need several adjustments for it to fit well in the mastery grading context.

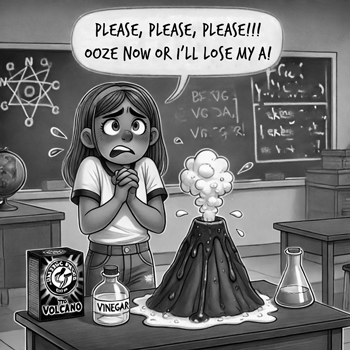

In traditional grading, projects often involve a single deliverable (a group presentation, a research paper, a bubbling and oozing faux volcano, etc.). Students usually have a week or more to complete a project and on the day it's due, it's due.

This traditional grading system is indicative of a fixed mindset. Students must complete their learning before doing the activities that are intended to help them learn. What?

In mastery grading, students have the opportunity to learn as they engage in learning opportunities. Perfection isn't expected immediately, and students have more than one shot to get it right.

Break It Up (Scaffolding)

But... a project will still culminate in a summative deliverable of some sort. How do you give students multiple chances to learn from one project? Break it up as granularly as you can.

Here are some ideas that have helped us with our projects. Pick and choose what's best for you, and, of course, sprinkle in your own creativity, too!

Set Multiple Checkpoints

For really large projects that span multiple weeks, we've had success with several "progress check" deliverables. For example, deliverables for a research paper might include:

-

CHECKPOINT 1: Thesis statement and set of sources. Objectives might include Source Selection and/or Clarity & Specificity. Instructors can give students feedback and allow them to iterate as necessary/viable.

-

CHECKPOINT 2: Set of facts from each source that support the thesis statement. Objectives might include Fact Extraction and/or Building an Argument. Again, instructors give feedback and allow students to improve.

-

CHECKPOINT 3: Outline of paper. The instructor might provide feedback on Logical Structure, Effective Use of Sources, and/or Flow. After receiving timely feedback from the instructor, students can improve their outlines for a few days before the Rough Draft is due.

-

CHECKPOINT 4: Full rough draft of paper. Instructors might look for things like Voice, Grammar & Word Choice, and Citing Sources, while revisiting any of the previous objectives as necessary. Students can rework their drafts until the Final Draft is due.

-

FINAL DRAFT: The final draft of the paper should reflect changes made in response to all feedback received in the previous checkpoints. All objectives will probably be assessed again at this time, though none of the assessments should be a surprise. Students have had many opportunities to gauge their level of mastery and improve their skills. Likewise, since the instructor will have reviewed all the previous submissions, the "final" assessment should be a breeze.

-

RESUBMISSIONS AS NECESSARY & POSSIBLE: Revisions to the final draft for those students who want to improve their assessments.

Sometimes resubmissions of the final deliverable are possible, and sometimes they're not. The summative nature of projects can make it difficult to schedule time for resubmissions, which is why the incremental checkpoints are so important. The learning happens at the checkpoints, so when the final deliverable is delivered, it should be almost anticlimactic.

Include a Peer Review Stage

Unfortunately, time is a zero-sum game. It can be difficult to give as much feedback as required in a timely fashion. Peer assessment can really help in these situations. Peer assessment will catch the glaring needs of the work, which must be addressed before the work comes to your desk. This reduces the number of resubmissions and let's you focus on nuanced detail.

Here are a few ways you can utilize peer assessment:

-

Let students explain their early project plans to a peer for initial feedback. Students learn from their own mistakes, yes, but they can learn from their peers' mistakes, too. If a peer's project proposal (e.g., the thesis statement) is too broad or unsupported by the sources, figuring out how to pivot is a great lesson regardless of who wrote the proposal.

-

Sometimes students are reticent to give constructive feedback to one another because of the potential loss of social capital. You can mitigate that by making helpful feedback a positive thing. Examples and gamification to the rescue! Give students a Feedback Bingo card, with fill-in-the-blank feedback sentences in each square (e.g., "I noticed that you focused a lot on ____, and that meant you focused less on __. How might you use the detail from ___ to make your argument more balanced?"). The more helpful feedback a student gives, the more likely they are to win a prize. Win, win!

-

Let students present their outlines to their peers to determine flow. You can keep it professional or let students be as silly as they want here. On-topic songs, comic strips, sports-like commentating, and post-it note mosaics are all great ways to organize and re-organize information.

-

If you can possibly free up a day in your course schedule, it is very valuable to teach students how to give and receive feedback with a growth mindset. Emphasize the difference between praise and positive feedback, as well as between criticism and constructive feedback. You can use whatever model of feedback makes sense to you. We love Brené Brown's "Man in the Arena" metaphor. It resonates deeply with our students and we hear them use the metaphor's terminology years after our courses end.

What About Presentations?

Presentations are a special type of project, and they almost always preclude resubmissions. It can be hard to schedule time in class for students to redo presentations (or pre-do them, as we've been advocating for).

They're vitally important for students' communication skills, though, so how do you make them work in a mastery grading classroom?

You can follow a checkpoint strategy much the same as the research paper example above, except the "Full rough draft" checkpoint is not a paper (obviously). It should be whatever you expect students to have ready at presentation time: a slideshow with the outline in the presentation notes section, a lesson plan with descriptions of the activities they're going to lead, a set of index cards with their major talking points, whatever makes sense in your course.

If the skills of presenting are included in your objectives (eye contact, not reading off slides/notes, etc.), you might consider using a day of class as a Presentation Teaser day. Students present only the introduction from their "first draft" equivalents, and leave their peers in suspense until the full presentation is given. This should be brief -- only 2 minutes per student or group -- and low-tech -- no fumbling with HDMI cables or slides. With this brief exercise, you can give students at least one chance to improve their presentation skills before giving their full presentations.

Looking Forward

In the next sections, we'll talk about making several other types of assessments mastery-grading-friendly, so you can keep your students learning and on their toes!