Assessment Opportunity Basics

We recently helped an instructor transform a traditionally graded course into one that uses mastery grading. Our word choice was careful there. The course was designed with a traditional grading (fixed mindset) lean. We mean no offense -- the course was creative and involved many active learning pedagogies -- but the assessment opportunities were designed with a focus on behavioral outcomes rather than course objectives.

In the limited time we had to work with this instructor before the start of the semester, we were able to modify the course to use mastery grading, but we didn't have time to refocus the assessment opportunities to better fit the mastery grading structure. Many of the objectives remained behavioral (presentation skills, writing skills, etc.), which limited the assessment of the actual course topics.

One of the assignments that we were not able to modify was a high-stakes in-class presentation. This presentation was previously worth 50% of the student's grade (when the course was in its traditional grading era), and it didn't allow for reassessment opportunities. With just one chance to design and present, the assessments were not indicative of student learning -- they were indicative of student perfection at a certain moment in time.

Suffice it to say, the assessment component of the course didn't go particularly well. Students were unhappy, grade calculations didn't feel accurate, and a lot of headaches ensued. We all learned a lot.

In this section, we provide a primer in assessment design for mastery grading -- one that would have helped that instructor (and us) make the tweaks necessary to provide meaningful assessment opportunities that also measure student learning.

Let's dig in!

Look At Your Existing Rubrics With a Critical Eye

Take a moment to find and study some of the rubrics you've used for assessment opportunities in the past, if you have any. Pay close attention to what is being assessed. Are you assessing course objectives, or are you assessing behavior?

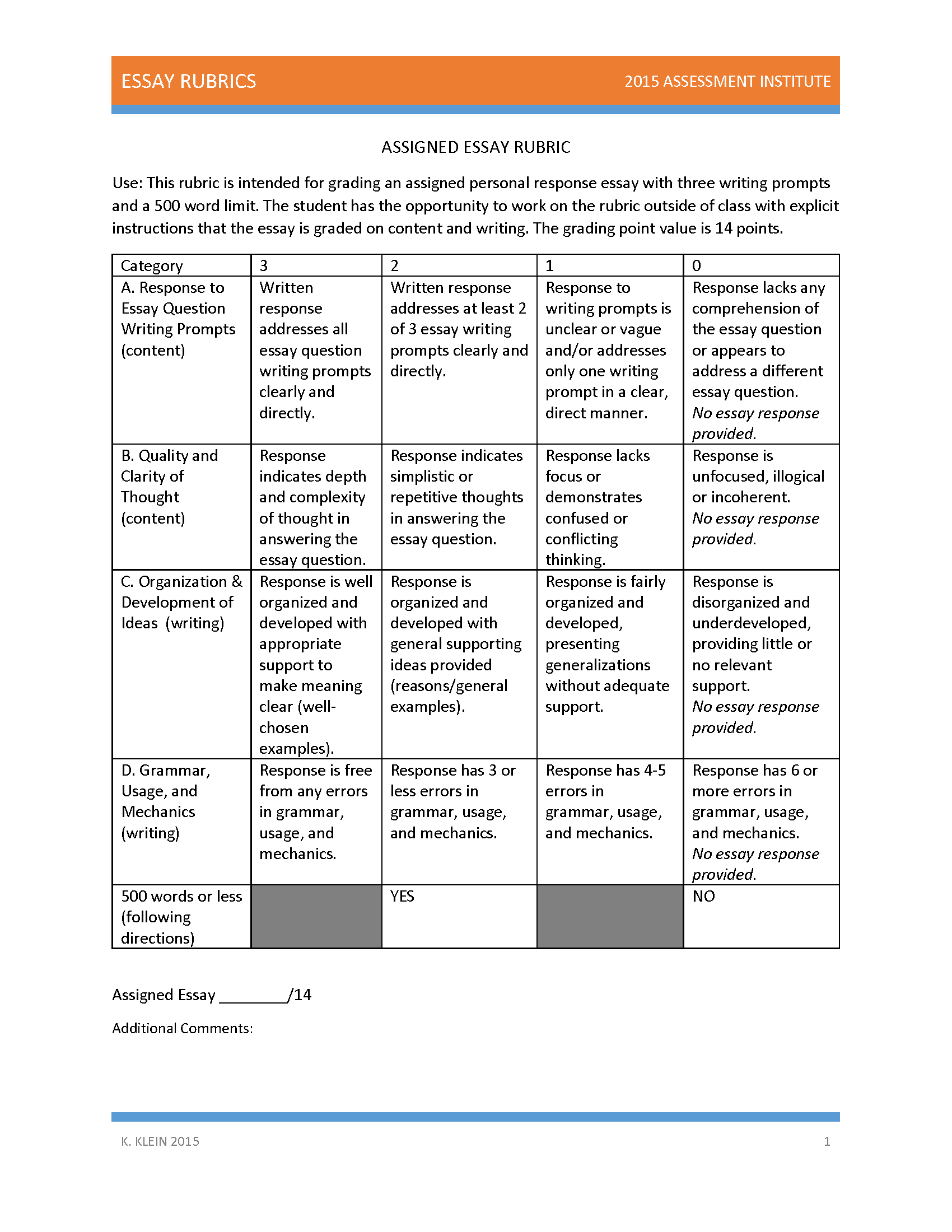

Let's look again at K. Klein's essay rubric.:

What is being assessed in this rubric is (in summary):

- Did you write about the thing I told you to write about?

- Did you think hard about the thing?

- Did you organize those thoughts the way I think you should have?

- Did you write in the formal register and make no errors?

- Did you follow directions?

At first glance, this looks somewhat reasonable. These are all fair questions to ask when reading an essay. But there's something very important missing from this rubric.

Let's say a history teacher assigns a 500-word personal essay on how the student’s understanding of genocide changed after watching a documentary. Would the rubric above be sufficient for assessing that essay? No, of course not. The rubric ignores the purpose of the assignment entirely.

The essay was probably assigned to assess the student's knowledge of genocide and the student's ability to recognize the lens through which they process historical information. The essay is how the students evidence their learning, but what's more important is what they've learned. The mechanics of the essay are important, yes, but they're hardly the point.

In mastery grading, each rubric item is a course objective. The chosen objectives should make the point of the assignment abundantly clear to students. Appropriate course objectives for the reflection essay might include:

- Impact of Genocide Critically analyze the historical, social, and political factors that have led to various genocides throughout history and express the impact of these events on affected populations.

- Lenses of Historical Narratives Analyze and evaluate the influence of cultural, political, and social contexts on historical narratives and critically assess the biases and implications of these differing viewpoints.

- Effective Historical Communication Construct well-supported arguments, engage in informed discussions, and utilize appropriate historical evidence to convey understanding of historical events and their significance.

Notice that the final objective sums up the entire previous rubric while also tying the communication to a purpose.

The point of this example is that rubrics sometimes look reasonable at first glance (and as we write them), but often they're assessing irrelevant and shallow aspects of student performance. We can do better.

Which Comes First? The Rubric or the Assignment?

Though it isn't ideal, in practice, the assignment usually comes first. Instructors think up a cool activity that relates to course material and then invest a great deal of time in writing clear specifications for what the student needs to do. The strategy for assessing the assignment comes much later, sometimes even after student work has been collected. At this stage, instructors are often grasping at straws as they try to figure out what it means to "get full points" for the assignment.

Designing assignments without understanding how they are to be assessed usually leads to shallow assessments.

"Did you get full points?" is an inherently different question than "Did you learn everything I expected you to?"

Most instructors would agree that in an ideal world, the rubric should come first. We've all probably attended a seminar that preached something to the effect of, "If you want to write effective assessments, identify what you want students to learn and then design a vehicle to get them there." In traditional grading, though, this seemed far too vague to be practical (at least for us). How do you make a rubric for a specific assignment without knowing the specifics of the assignment?

In mastery grading, making rubrics is easy because the rubric items are ready-made. They're the course objectives. So, when it comes time to design assessments, you get to shop through your objectives to find a subset that seems appropriate for the topics you're discussing in class. Then, design an assessment that allow students to showcase those objectives!

(We realize that we just told you "Just design it!" without telling you how. We'll get to that, we promise! If you're antsy, check out the following sections for best practices for designing projects, presentations, homework, exams, and participation assignments.)

What makes a "Good" Assessment Opportunity in Mastery Grading?

In general, a good assessment opportunity in mastery grading allows students to do something relevant, to receive actionable feedback to improve their performance, and to apply that feedback for improved mastery.

Applied, Authentic, & Relevant

Good assessment opportunities in mastery grading provide students authentic and applied opportunities to learn the subject matter from the master (that's you!).

If it helps with your brainstorming, you can evoke the role of a blacksmithing master, slowly training their apprentice to appreciate and replicate the nuances of their craft.

Thinking up assessment opportunities is the fun part (at least for us)! Think about the "masters" of your subject area. What sort of artifacts do they build? What sort of inferences do they make? If a TV news journalist interviewed them on air, what sort of questions would they need to answer?

If inspiration isn't flowing, go back to the set of objectives you want the assessment to showcase. When you wrote the objectives, you chose a verb from Bloom's Taxonomy ("analyze," "compare and contrast," "design," etc.). Think up a scenario where students can do that verb. Find or create a case study for the students to analyze, give them two nuanced examples to compare and contrast, or give them requirements of an artifact they need to design. When in doubt, look back at your objectives.

Objectives Are Assessable

Speaking of objectives, it is vitally important for an assessment opportunity in a mastery grading course to allow students to perform at varying levels of mastery for each objective.

- Can you imagine what an exemplary submission would look like?

- A satisfactory one? Are students given the opportunity to make mistakes?

- Would you be able to give the student clear, actionable feedback to help them cultivate their mastery if they didn't show it right away?

Avoid assessment opportunities that rely on an intangible sense for what is sufficient during assessment. (You know, like the time you got a 95% on a research paper and the instructor couldn't tell you why. "It's just not A+ work," he told you. Don't be that guy.)

Imagine the feedback you would give to a student who hasn't met mastery yet, for a student who met baseline mastery but still has room to improve, etc. If you can't imagine what kind of feedback you'll give, you probably want to rework the assignment until you can.

Opportunities for Growth

Finally, it's important for assessment opportunities to be learning opportunities. Notice the gerund there -- learning. Learning is an action or a process, not a singular outcome at a specific moment in time. So, assessment opportunities should allow students to perform, receive actionable feedback, revise, and repeat.

High-stakes, single-attempt assignments (like the presentation "worth 50% of the student's grade" that we mentioned above) are not well-suited to mastery grading.

How Many Assessment Opportunities & What Kind

There is no hard-and-fast rule for how many assessment opportunities a course should offer, nor for what type of opportunity is the most appropriate. Every course, instructor, and student population is different and has different needs.

If you've taught your course before (or taken a similar one), you probably have a sense of how much work your students need to (and have the capacity to) do to learn your particular subject matter. With that in mind, consider the implications of mastery grading on student time.

As a general guideline, a mastery grading course should have slightly fewer summative assessments (large, project-based or exam-type assessment opportunities that tie a bunch of objectives together) than a traditional grading course. Because mastery grading holds student work to a higher standard, students will spend a significant amount of time reworking and improving their mastery on previous assignments as they strive for the grade they want.

Formative assessments (small single-objective assessment opportunities offered as an opportunity for students to practice new skills) should also be offered slightly less frequently than in traditional grading courses. The low-stakes practice provided by formative assessments is essential for making students feel that it is safe to make and recover from mistakes as they learn. But, that recovery takes time.

Finally, if you choose to include participation assessments in your course, we recommend that you offer lots and lots (and lots) of opportunities. Consider providing a wide variety of opportunities for students to contribute so a diverse population of students can equitably and confidently contribute to the course community.

Looking Forward

In the next several sections, we discuss our experience with the most common types of assessments. We share what works well for us, what we've learned to avoid, and how you can make your favorite traditionally-graded assessments into mastery-grading friendly masterpieces.