Converting from Mastery to Letter Grades

In a perfect world, letter grades or other grade distinctions wouldn't exist. As we discussed in Why Mastery Grading, letter grades were originally created to permanently sort students into tiers of the factory organization (businessmen, managers, floor workers, etc.). Thank goodness, that's not the goal of education in the twenty-first century. We would probably revolt. We're writing and you're reading this guide because you care about cultivating your students' learning, not about permanently sorting 66% of them into inescapable poverty.

Nevertheless, most of us are beholden to the rules of our educational systems (schools, school districts, colleges, universities), and those educational systems demand grade distinctions1 for each student at the end of a term.

Since mastery grading doesn't include points or percentages, the conversion from mastery to grade distinction is a little more nuanced. There are many strategies for handling the conversion, but we'll talk about the three most popular options.

Mastery-to-Grade Option 1: Subjective Assessment

The first option for converting student work assessed with mastery grading techniques emphasizes the instructor's role as domain expert. The instructor looks at the collection of a student's work and subjectively assigns it the grade distinction they think is appropriate. This is most common in elementary schools, since more complex grading systems are harder for younger students to understand.

Mastery-to-Grade Option 2: Ungrading

There is a growing movement in the assessment community called "ungrading." Instructors who subscribe to this methodology believe that grade distinctions are so disconnected from the student's learning experience, instructors shouldn't assign grades at all.

However, because instructors need to provide some sort of grade distinction to meet the requirements of their institutions, they allow their students to choose and justify their own grade distinctions at the end of the term. Of course, instructors can challenge students' justifications (a student who hasn't provided evidence of mastery can't expect to request an A+ unchallenged). By and large, though, instructors that subscribe to ungrading say that their students most often choose a grade distinction on par with or lower than what the instructor thinks the student deserves.

Mastery-to-Grade Option 3 (Recommended): Portfolio Thresholds

The portfolio thresholds approach to converting mastery levels to grade distinctions focuses on the summation of the student's work throughout the term. As a student completes assigned work (and re-completes it if the student wishes to improve their assessments), the best sample of each assessment opportunity (homework, exam, etc.) gets added to the student's portfolio.

At the end of a term, the mastery levels (we'll call these ratings) earned for each assessment opportunity in the portfolio is checked against a set of thresholds set by the instructor that determine the student's final grade distinction.

This process is straightforward once it "clicks," but it can take a bit to wrap your head around it. Let's dig deeper!

What's the Portfolio?

A student's portfolio of work (sometimes also called a "bundle" of work) is the collection of assigned work the student has completed in the course.2 Only the best version of each assessment opportunity is included in the portfolio -- if the student resubmitted Homework 2 and received improved mastery levels, then only the higher scoring version of Homework 2 is included in the portfolio.

Okay, so how do we get from portfolios to mastery grades?

Requirements

We start with a short set of requirements. Instructors create a set of requirements that can be used to calculate grade distinctions for their course. Requirements are simple statements that specify that for [some objective], students need to earn [some quantity] of a specific mastery level in order to earn [some grade]. You've seen some version of these requirements before in the conversion of traditional grades into grade distinctions. In that case, the requirements look like:

- In order to earn a(n) [grade distinction] students must earn at least [some percentage] in the course.

Once we fill in the blanks of that statement, you get a traditional grading scale that looks something like this:

- In order to earn an [A], students must earn at least [90%] in the course.

- In order to earn a [B], students must earn at least [80%] in the course.

- In order to earn a [C], students must earn at least [70%] in the course.

- Etc.

The requirements for mastery grading are similar, except that there are often multiple requirements per grade distinction. Having a set of requirements instead of a single requirement allows your grade distinction calculations to be more nuanced and to challenge the students more than in traditional grading. If the goal of your course is to prepare students for the next course (or next great adventure), students must show evidence of mastery in every area of your course in order to earn a high grade distinction. It is not enough to just show mastery on average. If they have major knowledge gaps, they won't be successful in their next course.

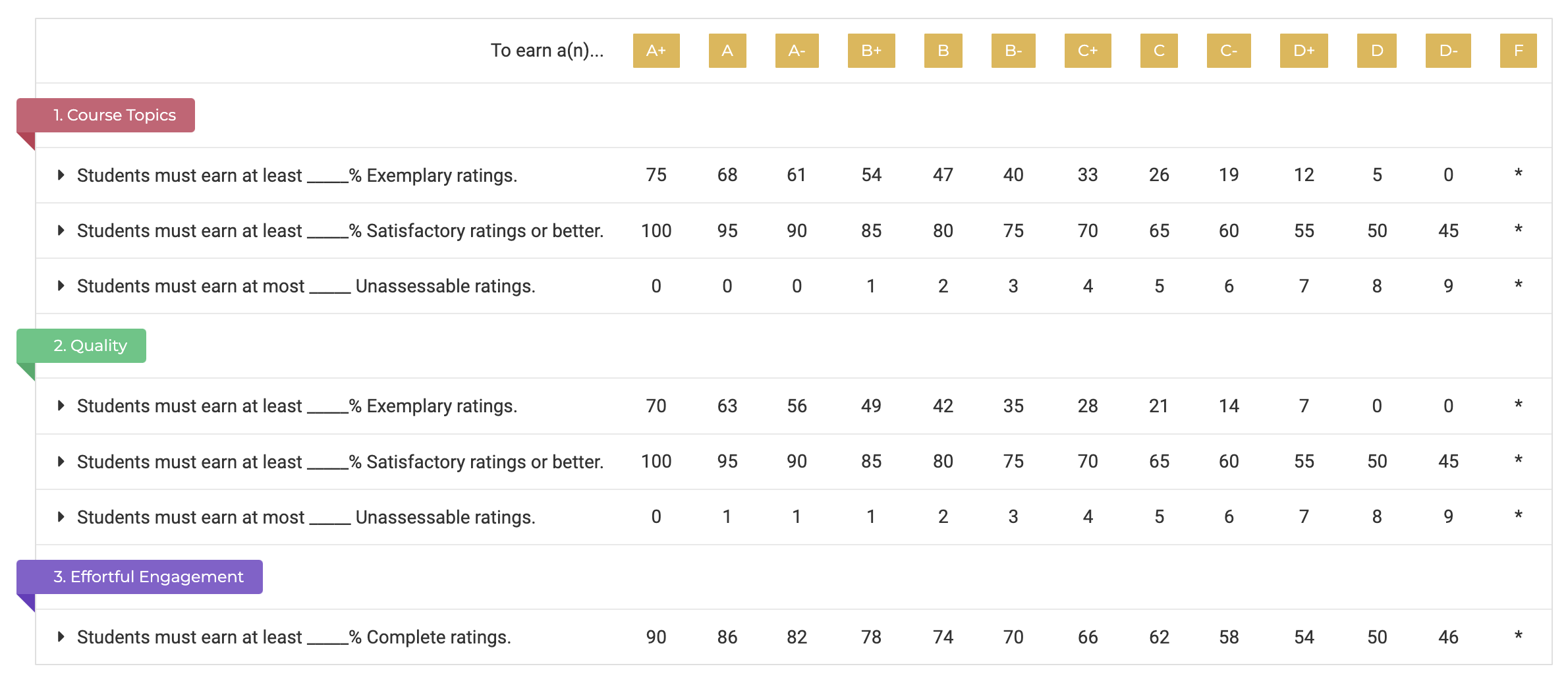

Naturally, the set of grade calculation requirements is entirely up to you. We know it can be much easier to edit, though, than to write from scratch, so we'll share the set of requirements that we use in our courses. We've experimented a lot with different requirements, but we've settled on a set that looks something like:

-

For the Course Topics objective:

- To earn a(n) [grade distinction], students must earn at least [some percent] of Exemplary ratings.

- To earn a(n) [grade distinction], students must earn at least [some percent] of Satisfactory ratings or better.

- To earn a(n) [grade distinction], students must earn no more than [some number] of Unassessable ratings.

-

For the Quality Objective: (notice that these are the same as the Course Topics objective, because they're both assessed with the same Mastery Level Scheme)

- To earn a(n) [grade distinction], students must earn at least [some percent] of Exemplary ratings.

- To earn a(n) [grade distinction], students must earn at least [some percent] of Satisfactory ratings or better.

- To earn a(n) [grade distinction], students must earn no more than [some number] of Unassessable ratings.

-

For the Effortful Engagement objective:

- To earn a(n) [grade distinction], students must earn at least [some percent] of Complete ratings.

How many requirements should you have? For each objective, you should probably have about as many requirements as you do mastery levels3. Consider the Course Topics and Quality objectives above. In our courses, those objectives are assessed with a four-level mastery level scheme (Exemplary, Satisfactory, Not Yet, and Unassessable) and so there are three requirements for each objective. The Effortful Engagement objective is assessed with a two-level scheme (Complete and Incomplete), so there is one requirement.

Thresholds

Great, so we wrote the set of requirements. Next, it's time to fill in the blanks.

For each of the grade distinctions given to us by our educational systems, we need to fill in [some percent] or [some number] in each requirement. You'll end up with a full set of requirements for each grade distinction. If you wrote all of those requirements out, it would take many pages and it would be pretty difficult for students to understand. We suggest making a table with the requirements as rows and the grade distinctions as columns. That way, you can fill in the cell at the intersection of each Requirement and Grade Distinction with the appropriate threshold.

We know -- it can be hard to visualize. Here's an example of a grade calculations table for one of our courses (an honors, college-freshman-level computing course):

In this example, to earn an A+, students must earn at least 75% Exemplary ratings, at least 100% Satisfactory ratings, and at most 0 Unassessable ratings in the Course Topics objective, etc.

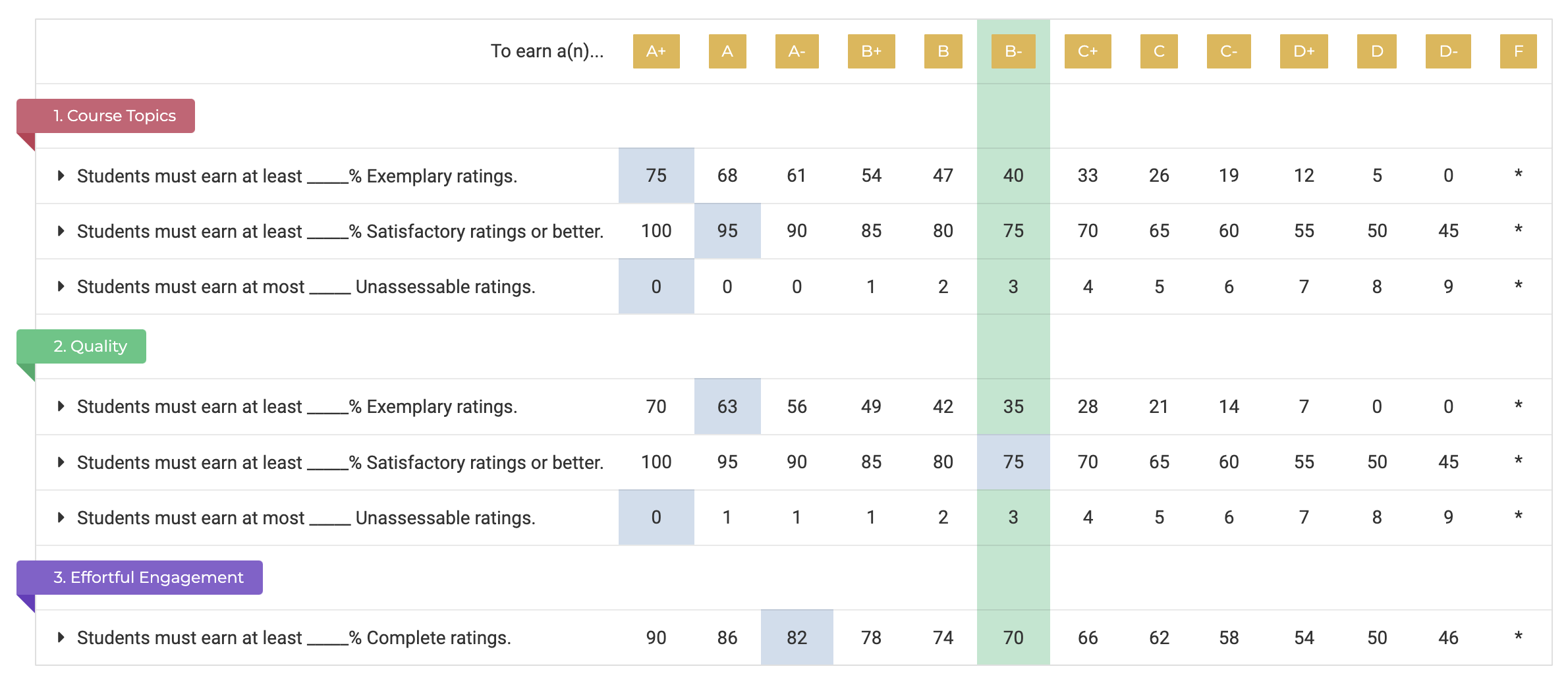

Given the tabular format, it can be easy to imagine that a student's work will neatly meet all the requirements for a single grade distinction. In reality, that's usually not the case. Sometimes a student will meet the threshold for an A in one requirement but the threshold for a B- in a different requirement.

Check out the table below that details a real student's grade calculation in one of our courses. The blue-shaded cells represent the highest grade distinction the student could earn for the requirement based on their portfolio. This student met thresholds in the A range for most requirements, but struggled to amass the same level of Satisfactory or better work in for the Quality objective (software testing, code structure, etc). In that requirement, the student only meets the threshold for a B-. Because the student's lowest grade distinction is a B-, the student's grade in the course is a B- (as indicated by the green-shaded column).

We can probably guess what you're thinking. It's probably something like, "That's too harsh!" or "It just doesn't seem fair!" If this is indeed what you were thinking, bear with us for just a bit.4

As we mentioned above, students must show evidence of mastery in every area of your course in order to be ready for the next course. It is a disservice to the student to simply average the grade distinctions and give them a false impression of their mastery and their prospects for future courses.

One would not want a doctor who performed really well in radiology, but performed poorly in pharmacology. No, you'd hope that someone told the doctor to study up on pharmacology before handing over a medical license. Determining grade distinctions in a course is much the same. Students must pursue growth in all areas in order to attain the grade they want.

Averaging student performance tells students that opportunities for their growth can be erased by the successes they've already found.

—Dr. Stephanie Valentine

Associate Professor of Practice and TeachFront Founder

Looking Forward

In the next section, we provide a resource you can use to explain grade calculations to your students, and in the section after that, we'll talk about how to create and fine-tune your threshold values.

Footnotes

-

We're using the term "grade distinctions" instead of "letter grades" because not all educational organizations use letters for their grades. ↩

-

Most of the time, the portfolio is metaphorical, but we have had success with having students build actual portfolios to showcase all of their work for the semester. It can be very helpful for job and internship interviews to have a portfolio of examples ready! ↩

-

Sometimes, requirements can be redundant. For example, the requirement, "Students must earn at least 75% Satisfactory ratings or better," is basically the same as "Students must earn no more than 25% Not Yet or below ratings." You don't need both requirements (though it isn't bad practice to include both). ↩

-

We often hear that mastery grading doesn't have the rigor that traditional grading has. Mastery grading just gives everyone a gold star so they can feel good about themselves. This is blatantly false. Mastery grading sets far higher expectations on the students than traditional grading does. Students receive additional opportunities to prove their mastery so they can meet those higher expectations. ↩